The Stourbridge Lion and the Birthplace of America's Commercial Railroad

In order to evaluate the use and power of the steam engines and the rails on which they were run, the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company sent a deputy engineer, Horatio Allen, to England in 1828. If he decided they would be suitable for the company’s use, he was instructed to place orders for four engines and rails.

Horatio Allen’s inquiries led him first to Newcastle, where the Stephenson family was producing an engine for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Allen was impressed and ordered one engine from them. He then went to the Town of Stourbridge where he met a brilliant engineer, John Urpeth Rastrick.

Rastrick had taken out a patent for the steam engine in 1814 and formed the firm of Foster Rastrick and Company to produce them. He was considered an authoritative witness in support of railroads when opposition from the canal companies threatened their growth and development .

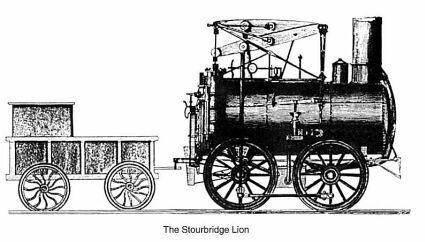

It was from Foster Rastrick and Company that Allen ordered the other three locomotives. Among them was the Stourbridge Lion, so named because a Lion’s head had been painted on the front of the boiler. It weighed eight tons and cost $2,915.00.

|

|

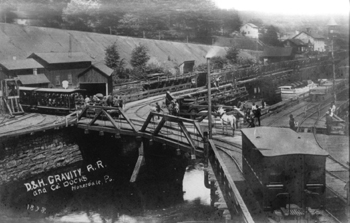

The trial run was to take place on the 8th of August 1829. When this became known, crowds of people assembled to witness the event, convinced that the iron Lion would never work. Afraid that the curious contraption would kill any who rode it, no one would take the trial run with Horatio Allen. So, amidst jeers and laughter, he mounted the hissing Lion. The jeers quickly turned to cheers as the Stourbridge Lion crossed the bridge and disappeared from sight. Many thought it would not return; but soon, with Allen at the throttle, and riding backwards, the fierce Lion screeched back into Honesdale. The crowd was jubilant. A new era in commercial transportation had begun.

After another trial, it was decided by the company that the light wooden rails would not stand up to the continued use of the locomotive and the haulage of coal, so it was put into storage in a shed at Honesdale. There it remained until 1849 when the company removed it to their workshops at Carbondale,

Pennsylvania. The boiler was removed and put to use, and other parts were removed and separated, some being irretrievably lost.

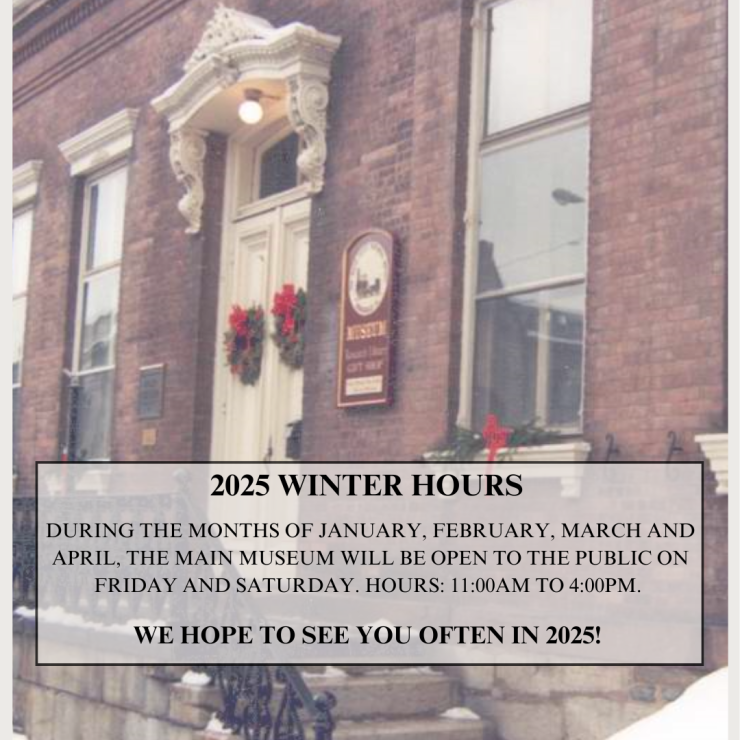

In 1889 another firm acquired the boiler and deposited it with as many of the other parts of the engine as they could find at the Smithsonian Institution. There it was partially reconstructed and stood in this form for many years in the Hall of Transport. The Delaware and Hudson Railroad Company has built a full scale replica of the Stourbridge Lion from the original plans. It is on exhibit at the Wayne County Historical Society’s, 810 Main Street, Honesdale museum, (570)-253-3240.

Visit our library for more information and photographs.

Navigation

News and Events